Ito Masatoshi (Assistant Professor, Department of International Liberal Arts, Nihon University College of International Relations)

Ridjojo Uchida (originally Uchida Ryozo, 1926–2008) was born in 1926 in Tanjung Tiram, a port town on the east coast of North Sumatra Province. His father (1895–1941) was Japanese, originally from Wakayama Prefecture. Having come to Sumatra during World War I, he decided to return to Japan in the late 1930s.

Ridjojo, a teenager during World War II, worked at the Imperial Guard Field Artillery 2nd Regiment Headquarters in Sumatra. Japanese by blood, he worked for the Japanese military during World War II and joined the Indonesian National Armed Forces during the Indonesian War of Independence (August 1945 to December 1949). After independence, he became a newspaper reporter in Medan, the capital of North Sumatra Province, mainly writing about Japan. He also worked to promote friendly Indonesia–Japan relations, mainly through educational and cultural exchange. In addition, he became close to first-generation Japanese-Indonesians, former Japanese soldiers living clustered in Medan and its surroundings. As a veteran of the Indonesian War of Independence, he was a fellow Japanese of the same generation.

This document includes a partial translation of Jembatan Emas Persahabatan Indonesia Jepang yang Abadi (The Everlasting Golden Bridge of Friendship Between Japan and Indonesia), a booklet produced by Ridjojo in 1992. Running to some 200 pages, it is composed of a preface, a certificate of Ridjojo’s service working for the Japanese Army during the war, a letter of thanks for his promotion of Indonesia–Japan amity, and a collection of newspaper articles (including ones written by his second and fifth daughters).

Below is an introduction to the preface and 13 newspaper articles. The preface and articles (1) through (8) are by Ridjojo, while articles (9) through (13) are by his daughter Mariko Djaya. The articles offer a glimpse of the human interactions between the people of Southeast Asia and those of “mainland” Japan, even in the midst of the ugliness of war.

The Everlasting Golden Bridge of Friendship Between Japan and Indonesia (Medan, January 1, 1992)

Preface

Assalamu’ Alaikum Wa Rahmatullahi Wa Barakatuh

Thanks be to Allah, and peace be with his prophet Muhammad and his family. Immeasurable thanks are owed to the government of Indonesia as well; we must never forget that the peaceful times we live in today are thanks to the heroes of the 1945 independence movement, who gave up their own lives in selfless struggle, under the motto “Liberty or Death.”

I, an old man now, hope to use my remaining years to pass on the spirit of ‘45 to the next generation. In my old age, as a veteran of the Indonesian Armed Forces (LVRI), I have been interacting with veterans from other countries, in accordance with the spirit of the “independent and active” Indonesian foreign policy. I have also been collecting articles and materials on tourism, so that younger people can understand its importance.

Currently, the Indonesian government is focusing on the promotion of the tourism industry; I would like to see people from around the world enjoy our sightseeing spots barely touched by the hand of man. Without the environmental protection and guaranteed safety needed to promote the tourism industry, these locations will go unnoticed by travelers. Therefore, it is important to educate children early on and enhance their environmental awareness. All I can do is to write reports on the tourists who visit this region.

Many of them are veterans like me, especially the former Japanese soldiers once deployed to Indonesia. Stationed in Indonesia during the war, they walked the land here in great suffering. Now they return as tourists, looking back on their experiences with nostalgia. There is a saying that goes, “tempat jatuh lagi dikenang, konon pula tempat bermain” (remember the places where you fell along with the ones where you played). Where there are memories pain there are also memories of joy. They have come to see these places of pleasure and pain once again before they die. This saying has influenced my spirit and my values. As more tourists come, they have begun to write commemorative sightseeing reports when they return home.

Visiting this place again was a dream come true for them. Rejoicing, they brought home reports on their feelings and experiences during the journey. After returning to Japan, they made copies of these reports to distribute to their relatives and friends. As this practice becomes more frequent, more tourists have begun to visit us.

In general, Indonesians do not resent Japan. They have completely forgotten their past conflict and the harsh treatment meted out, and are now intent on working toward mutual aid as friends for the benefit of both countries. Therefore, many of the visitors consider Indonesia their second home and talk about wanting to live here.

From the 1970s, I have devoted myself to writing reports on tourism, conducting Japan–Indonesia interchange through exchanges of songs, dance, children’s pictures, and so on. I also teach origami to Indonesian students, women’s groups, boy scouts and so on. Children who learn about each other’s cultures will remember that experience when they grow up, continuing exchange with the other country on the individual level. This is why I chose to entitle this document Jembatan Emas Persahabatan Indonesia Jepang yang Abadi (The Everlasting Golden Bridge of Friendship Between Japan and Indonesia).

I wish to express my gratitude to the people of Indonesia for their understanding of these materials and their love of peace. My thanks and prayers go to my parents, who provided me with general and Islamic education, as well. I am also grateful to all our visitors from Japan, especially those involved with these documents, and wish them the best of health and fortune. I pray for the rest of the souls of those who have already passed away.

I hope my own children will continue to pursue their dreams. I believe that Allah will smile on those who treat others with kindness as fellow human beings and avoid wrongdoing. Hablum minallah, hablum minanas:There is harmony between God and man.

I am also grateful to my wife for her constant devotion and support. With her sincere encouragement, I hope I may remain on the true path, complete these materials, and be of help to others. With love and gratitude for our children, I hope they will carry on this dream.

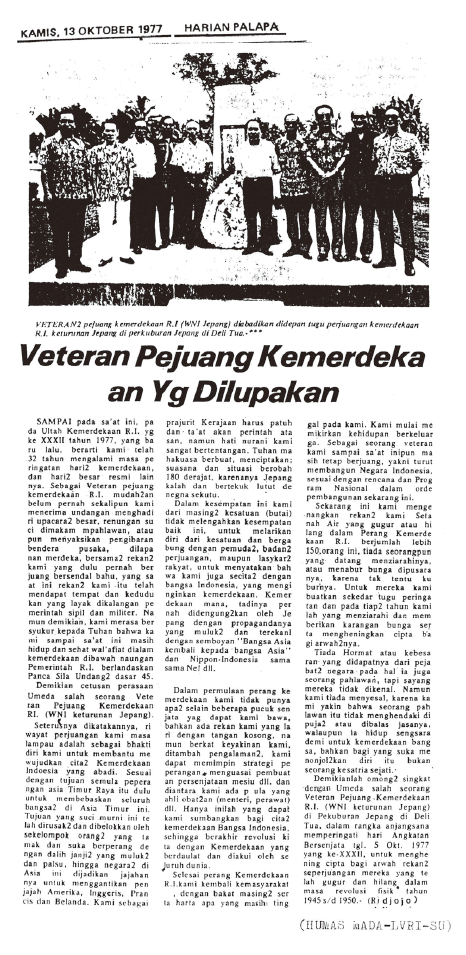

(1) Harian Palapa (Daily Palapa) (Thursday, October 13, 1977)

Forgotten Veterans of the War of Independence

In 1977, Indonesia celebrated 32 years of independence. We are commemorating our 32nd year as an independent country. We veterans of the Indonesian War of Independence have not once been invited to any of the major events celebrating independence, such as the memorial service at the Heroes Cemetery for those who perished in the war, or the event at Merdeka Square. Many of our wartime comrades have become government officials. I thank Allah for being alive and healthy under the Indonesian government of today, with the 1945 Constitution and the Pancasila philosophy of Five Principles upholding the country.

Below are the thoughts of Mr. Umeda, an Independence War veteran (a Japanese-Indonesian).

I have fought thus far to contribute to Indonesian independence, just the same as the purpose of the early days of the Greater East Asia War—to free the countries of East Asia. This noble purpose was put to ill use by a group of greedy warmongers. Like the Americans, British, French and Dutch, they colonized the countries of Asia. I followed orders as a soldier of the Imperial Japanese Army, but in my heart I was protesting. Afterward, the hand of God turned the situation by 180 degrees, and Japan was defeated.

We did not miss this perfect opportunity. We deserted our units and joined the troops, militias, youth groups and so on fighting for Indonesian independence, dreaming the same dreams as they did and vowing to realize independence for Indonesia. This independence was in line with Japan’s proclamations of “From Asia to Asia” and “Let Japan and Indonesia be together.”

When we fought in the War of Independence, all we had were the weapons we were carrying. Some of us deserters had nothing at all. But we had the courage of our convictions and our previous experience of war; we taught our new comrades how to fight, how to make gunpowder, and so on. Some of us, knowledgeable about medicine, became combat medics. We had no other way to contribute to Indonesian independence.

After the war, we became civilians again, making a living with whatever skills we had. We still follow the national program as veterans, fighting on for national development.

We remember our 150 comrades who fell or went missing during the War of Independence. No one came to visit their graves; some have no graves at all, not even any flowers left for them. Therefore, we have built a memorial for them, bringing them flowers every year and praying for the rest of their souls.

It is a great shame that these heroes have never been recognized by the government, with even their names remaining unknown. But we have no regrets. Heroes don’t need words of praise or honor. We suffered for independence, but we have no regrets. Real heroes don’t brag about what they have done.

This is the story I heard from Mr. Umeda, a Japanese-Indonesian veteran of the War of Independence, at the Japanese cemetery in Deli Tua. In commemoration of the 32nd anniversary of the Indonesian Army, I offer a silent prayer for our fallen comrades of 1945 to 1950. (Ridjojo)

(2) Analisa (Thursday, May 26, 1977)

Eight Japanese Tourists Visit Japanese Cemeteries in Aceh

Yesterday, eight Japanese tourists from Osaka and Tokyo traveled from Medan to Aceh on an F-28 jet in order to visit the Japanese graves in Banda Aceh and Sabang.

They also visited various places of historical significance in Indonesia. The visitors were former Japanese soldiers of the 65th Sumatra Corps. The purpose of their visit to North Sumatra and Indonesia in general was to see the towns and buildings where they had been stationed. While traveling to Sibolga, Parapat, and North Tapanuli, they stopped at the Sibolga Highlands, where they had often spent free time while stationed in Medan. Led by Mr. Inada, the eight Japanese tourists included Mr. Hirase, Mr. Fukugawa, Mr. Igarashi, Mr. and Mrs. Ike, and Mr. and Mrs. Gonyasu.

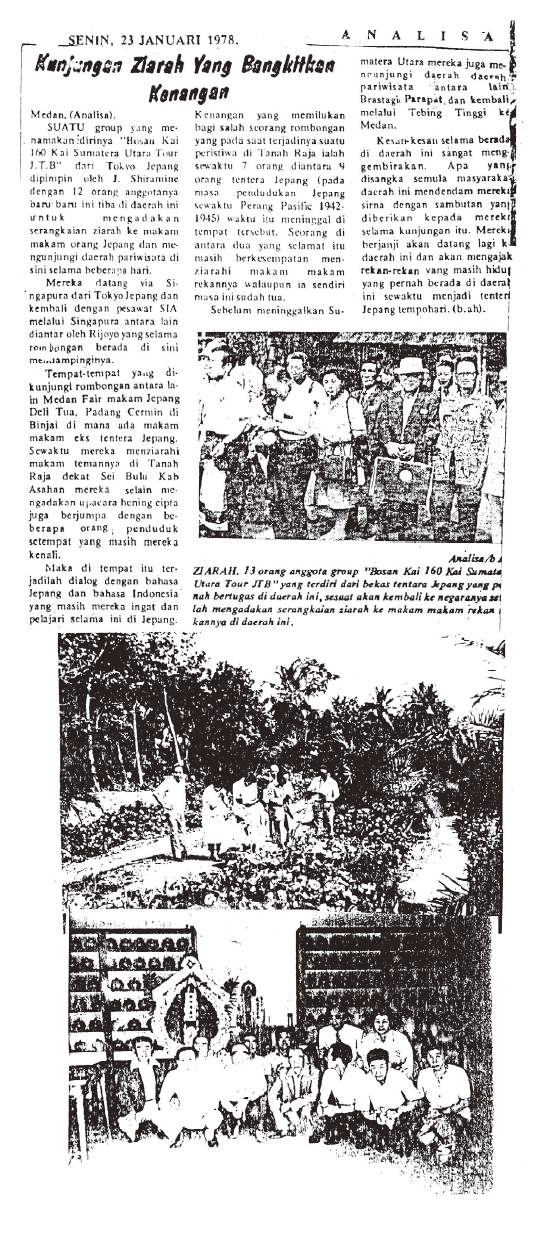

(3) Analisa (Monday, January 23, 1978)

Visiting Memories

Led by Mr. Shiramine, a 12-member tour group called the 160 Grave Visits North Sumatra Tours JTB visited North Sumatra in order to pay respects to Japanese cemeteries.

They flew from Tokyo via Singapore Airlines, seeing the sights as well as visiting graves. Ridjojo acted as their guide. They visited Medan Fair as well as the Japanese cemeteries at Deli Tua and at Padang Cermin in Binjai. When traveling through the Tanah Raja basin in Asahan Regency (near Sei Bulu), they encountered residents familiar with them. They were able to chat with the local residents, mixing Japanese and Bahasa Indonesia. One of the tour members recalled the terrible experience of his deployment to Tanah Raja.

During the Pacific War from 1942 to 1945, seven of the nine Japanese soldiers stationed at Tanah Raja died there. One of the two survivors folded his hands before his comrades’ graves, praying for the repose of their souls. Before leaving North Sumatra, they visited sightseeing spots such as Berastagi and Parapat and then returned to Medan City.

They were very impressed by their visit to North Sumatra. At first they had been concerned that the Indonesians would hate Japanese, but the welcome given them by local residents dispelled their fears in an instant. They promised to bring back other comrades dispatched to Indonesia during the war.

(4) Newspaper unknown (Wednesday, February 22, 1978)

Pematangsiantar, City of Memories

On February 16, 1978, Kinpo Sumatra Tours, a group tour from Tokyo, visited Japanese cemeteries and local sightseeing spots. Led by Mr. Ebashi, the tour group was 22 strong. They flew from Tokyo on Singapore Airlines. Ridjojo served as guide and interpreter for their visit.

On the first day, they paid a courtesy call on Siantar City Mayor Sanggup Ketaren. They greeted the Mayor as follows. “We fondly remember living in Pematangsiantar 35 years ago, as well as our interactions with local residents here. Over these 35 years, the city has changed a great deal, but some of the same buildings still remain. We are grateful for the Mayor’s welcome.” The Mayor offered the visitors a warm welcome and hoped that they would return again to North Sumatra with more friends. Finally, there was an exchange of commemorative gifts and a photograph taken in front of City Hall. Mr. Ebashi made conversation using the Bahasa Indonesia he remembered, keeping the event lively.

On the second day, they visited the mission junior high school on Jalan Gereja at nine in the morning or so, where they were welcomed at the entrance by girl students clad in the traditional dress of the Simalungun region. They enjoyed a display of traditional dancing by the students before entering the school auditorium. There the principal, Mr. Sitorus, greeted them in English and Japanese. The tour members were favorably impressed that there were Indonesians who could speak Japanese in such a secluded location.

Next, Principal Sitorus placed an ulos cloth (the traditional woven textile of the Batak people) on Mr. Ebashi as tour representative, and everyone expressed welcome with three cries of “horas.” In his greeting, Mr. Ebashi said that such an unexpected welcome tempted him to settle down in Indonesia without ever returning to Japan. He said that Pematangsiantar was like another hometown for him. Mr. Ebashi also expressed his appreciation to the school thus: “During the war, I once lived in this school, and I’m very happy to have seen the original building just as it was. I hope the students will grow up to be people who can do good for their country and for others. Finally, I hope the friendly relations between Japan and Indonesia will continue forever.”

Various songs and dances were performed. The visitors were especially interested in the Japanese song “Aikoku no Hana” (“Flower of Patriotism”) sung by a girl named Yunita. Asked to sing along, they declined based on not knowing the lyrics. In response to a request from a school official, Ridjojo came forward and sang along, receiving enthusiastic applause. Finally, the group presented the school with souvenirs from Japan (stationery items, soccer balls, etc.).

After taking a commemorative photograph, they traveled to Parapat. On the final day of their trip, they met with the Medan Lions Club at the Danau Toba International Hotel in Medan. The famous Medanese painter Sinaga was also present. The Medan Lions Club promised to distribute the donation received to people in need. On the morning of February 19, 1978, they returned to Japan at the close of a memorable trip.

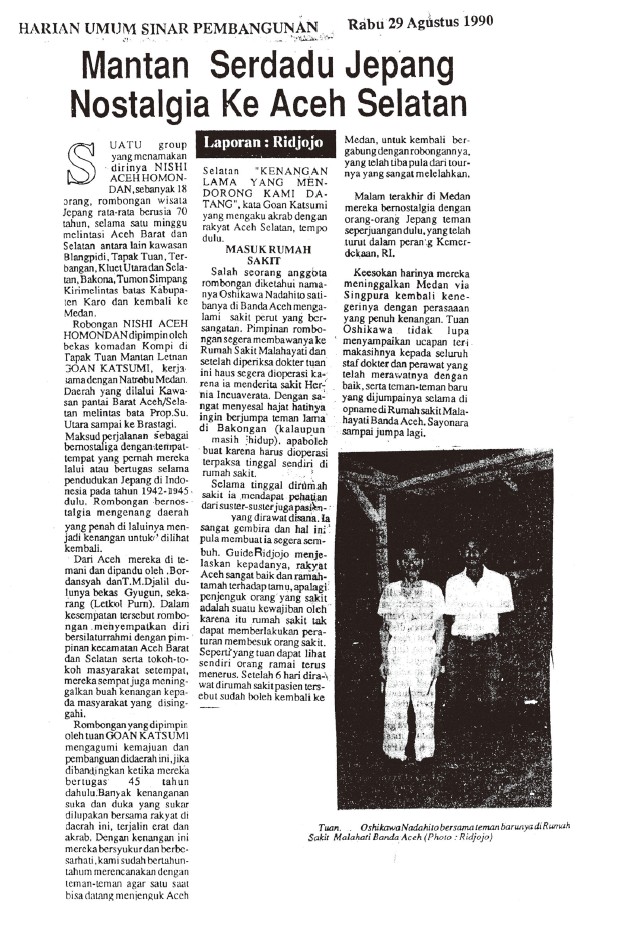

(5) Harian Umum Sinar Pembangunan (Daily Sinar Pembangunan) (Wednesday, August 29, 1990)

Former Japanese Soldiers Pay a Nostalgic Visit to Southern Aceh

An 18-member Japanese tour group called the Western Aceh Visiting Group spent a week touring western and southern Aceh. The group’s average age was 70. They traveled through the Blangpidie region, Tapak Tuan, Terbangan, Kluet, Bakona, and Tumon Simpang before crossing the Karo Regency border and returning to Medan.

The tour leader was former Tapak Tuan company commander Lt. Katsumi. They used the Medan Natrabu Travel Agency. The purpose of the tour was to revisit the places they remembered from their 1942–1945 deployment to Indonesia.

While visiting Aceh, guided by veterans Bordansyah and Djalil, they were able to exchange greetings with officials and regional leaders in western and southern Aceh. They were surprised by Aceh’s development over the intervening 45 years. They have never been able to forget the time they spent with the Acehnese during the war (whether in joy or pain). This visit has apparently been planned for several years. “We came here because it is the place of our memories from long ago,” Katsumi recounted.

Hospitalization

After arriving in Banda Aceh, Mr. Oshikawa developed a stomachache. Diagnosed with a strangulated hernia, he was admitted to Malahayati Hospital for surgery. Because of this hospitalization, he was unable to visit friends in Bakongan. After six days in the hospital, he was discharged and rejoined the tour group.

On the last evening of the tour, there was a reunion with former Japanese soldiers who had joined the Indonesian Army during the War of Independence. The next morning, the tour left Medan to return to Japan via Singapore. Mr. Oshikawa said that he was grateful to the doctors and nurses who had treated and cared for him kindly at Malahayati Hospital, as well as the fellow patients and others he had encountered there. Goodbye. May we meet again.

(6) Harian Umum Sinar Pembangunan (Daily Sinar Pembangunan) (Saturday, September 15, 1990)

Diary: Former World War II Japanese soldier Matsui Toshio (translated by Ridjojo)

An 18-member Japanese tour group visited North Sumatra on a “journey to encounter nostalgic Sumatra once again.” Born between 1914 and 1921, they were elderly but sturdy and energetic. Their tour began in North Sumatra and took in West and South Sumatra before concluding with Bandung and Jakarta in Java.

After arriving at Palembang in South Sumatra, they toured Sumatran sightseeing spots by bus and then went on to Bandung and Java, likewise by bus. Their guide, Ridjojo, received a diary of the tour from the tour leader, Mr. Matsui Toshio, and translated it into Bahasa Indonesia. In accordance with the governmental “Indonesia Tourism Year 1991,” Indonesians are expected to become more tourism-aware.

August 20, 1990

Today we arrived in my beloved Sumatra. It has been 45 years since I left the artillery regiment in March 1945. From Changgi Airport in Singapore, it took only an hour and ten minutes to reach Polonia Airport in Medan. That’s just a little longer than the flight from Tokyo to Osaka. Northern Medan is where Belawan Harbor is, where the artillery regiment had landing privileges during the war. This time there isn’t enough time to visit Belawan.

The exchange rate is one US dollar to 155 yen, converted to 1,772 Indonesian rupiahs. I was surprised to get back 180,000 rupiahs for 100 US dollars. After sightseeing in Medan, we passed through Tebing Tinggi and Pemangsiantar on our way to Parapat. I remember using the same route during the Japanese colonial era. We saw houses, railway lines, farms and so on.

However, the Berastagi route and its beautiful scenery were a new experience this time. According to the pamphlet on North Sumatra tourism given us by the travel agency, Lake Toba has become a country-house area at 920 meters altitude. Samosir Island, in the middle of the lake, is inhabited by the Toba Batak people and has many historical remains.

During the war, it was a concentration camp for Dutch women and children. Ambarita Village, on the island, has on display the stone throne once used by the kings (nobles) of the Batak people.

Tonight we are staying at the Parapat Hotel, which compared to the hotel in Singapore is… well, not that bad.

August 21, 1990

Today we traveled through Tarutung and Sibolga to Padang Sidempuan and its many good memories. Traveling southeast from Parapat, we arrived at Porsea, where the water from Lake Toba runs into the Asahan River. On the Asahan River is a dam built with aid from Japan, used as a hydropower station. Many Japanese were involved in the construction of the dam, as a technology transfer to Indonesia.

Next we traveled through Balige, Siborong-borong, and Tarutung. In the Japanese colonial era, there was a Japanese sake company in Siborong-borong called “Chousen” (“Challenge”), which was then very well-known. Tarutung has hot springs which are very popular with Japanese, but Indonesia has not done much with them, as Indonesians don’t visit hot springs.

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions and the supply regiment were deployed here as well. Other deployments included training for drivers from the artillery regiment. After leaving Tarutung, we went up and down the Bukit Barisan mountains until the Indian Ocean became visible in the distance. Then we passed through a short tunnel to arrive at Sibolga. This was apparently the only tunnel in Sumatra.

Sibolga had a live firing range for training, where the 2nd and 5th companies (the 25th Merdeka Joint Brigade) were once deployed. After that, we arrived at Padang Sidempuan, which has been known for a long time as a residential area. I was interested in the occupations and sources of income of the residents. I wasn’t able to see the remains of the buildings once used by the Japanese army, such as the barracks and mess hall. At the entrance to the town is a sign reading “Padang Sidempuan: Town of Snake Fruit.” Once the commander’s mansion stood before that sign. Padang Sidempuan was once under the jurisdiction of the Tapanuli Regency, but it is now in North Sumatra Province.

(continued)

(7) Harian Umum Sinar Pembangunan (Daily Sinar Pembangunan) (Monday, September 17, 1990)

Diary: Former World War II Japanese soldier Matsui Toshio (translated by Ridjojo)

Our Welcome in Padang Sidempuan, Town of Snake Fruit

When we arrived at the Samudra Hotel, we were immediately invited to a Mandailing-style welcome party. A representative of our group became the “king,” with a pretty local woman as his queen. According to Ridjojo’s explanation, visitors are welcomed like kings in the Mandailing region. The guest was given a traditional costume to wear, with a kris (traditional dagger) in his belt, sitting alongside the woman in the queen’s role. Retainers lined up behind them. Drums and flutes sounded and we heard pantun (traditional poetry) being recited. With the explanation provided, the tour group was finally able to understand the situation. The king and queen danced the traditional tortor with everyone, and then gave a toast. “Horas!”

The king-for-a-day, Mr. Hiura, born in Wakayama Prefecture on October 15, 1914, was moved by the welcome. He said that he would never forget this Indonesian interlude.

August 22, 1990

From Padang Sidempuan, we traveled along the Bukit Barisan to Bukittinggi. We managed to cover 517 kilometers today. Compared to the Japanese military era, the roads now are wide and well cared for, but the side roads and mountain-climbing paths are still pretty much the same. We passed a gold mine (gold dust) on the way. There were several new high-altitude towns along the way; near the Equator signpost in Lubuk Sikaping, the road widened.

We traveled from the ancestral lands of the Batak people to those of the Minangkabau. A little south of Lubuk Sikaping, we arrived at Bonjol, famous for its Equator signpost. We stopped to see the signpost. On the left side of the road there was a large building in the style of traditional Minangkabau houses, known as the Imam Bonjol Museum. Across the road on the right there was a large gathering hall, with a footbridge connecting the two.

We received a certificate from the Natrabu Travel Agency in commemoration of crossing the equator. As Mt. Merapi (2,891 meters) was now in view, we knew we were almost at Bukittinggi. Once the 25th Army had a base at Bukittinggi, but I don’t know if that building remains, or if so what it is used for now.

(8) Harian Umum Sinar Pembangunan (Daily Sinar Pembangunan) (Tuesday, September 18, 1990)

Diary: Former World War II Japanese soldier Matsui Toshio (translated by Ridjojo)

Bukittinggi, also known as the Thousand and One Nights, is cool in temperature. The Dutch Governor-General used to live here as well. The Minangkabau region, Sumatra’s West Coast Province during Japanese colonial times, is now West Sumatra Province. Many historical buildings such as the Dutch fortress and clock tower remain in the town, which is an Indonesian cultural heritage site. Bukittinggi was once called Fort de Kock (named after the Dutch hero who conquered the town).

To the west is the Sianok Gorge, a famous sightseeing spot, where the giant rafflesia flower blooms. A replica rafflesia made of rubber and plastic, identical to the real thing, is on display in Osaka’s Tsurumi-Ryokuchi Park.

August 23, 1990

Today’s schedule took us from Bukittinggi through Solok, Sawahlunto, and Indarung to Padang. About 40 kilometers from Bukittinggi, the road forks for Padang Panjang. We took the western route past a waterfall to arrive at Padang. The eastern route goes past Lake Singkarak to Solok.

Note that “Solok” has a K at the end; it is not the same as the one in the famous song “Bengawan Solo” (“Solo River”). From Solok we turned east and went about another 40 kilometers to Sawahlunto.

I worked in Sawahlunto first when I was attached to the 2nd Battalion, and last for Sumatra Central Railways. Ombilin still has a thriving coal mining industry. Going southwest from Ombilin, we arrived at Indarung. The cement manufactured here is transported as far as Teluk Bayur Port in Padang. The 4th Artillery Corps and its companies (except the 1st Company) were deployed to Indarung at one point. Indarung was where Lt. Watanabe died in an air raid by the Allies. At the time of our visit, there were no barracks left. We went down from Indarung into Padang.

Padang City Facing the Indian Ocean, Padang once housed a base for the 4th Japanese Army. To the north are Tabing Airport and the Muara Hotel (once the Daiwa Hotel). The 4th Regiment was assigned to duties near the airport in the Gunung Pangilun region. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 92nd Highland Corps and the Anti-Aircraft Regiment were sent from Padang Sidempuan as a defense force for the area.

The first commander was Lt. Hiraishi, followed by Lt. Ida and then Lt. Sakuma. There was a 15cm anti-aircraft gun facing south on a hill near Teluk Bayur Port. The Anti-Aircraft Regiment commander was Lt. Hasegawa of the 1st Battalion, a weapons specialist. The defense force under Lt. Higashiguchi was deployed to Gunung Pangilun. According to the residents, there was a bunker at the top of Gunung Pangilun, but it is now a residential area.

Around the end of the war, the 15cm gun was transported to Pariaman near Padang, where Lt. Fukumoto replaced Lt. Higashiguchi as commander. In April 1945, there was an unexpected attack from an enemy submarine. The fuel tanks were destroyed. The 15cm gun could not be used to return fire on the submarine.

August 25, 1990

The tour group arrived at Teluk Bayur. Reminiscing about the past, we looked across at Cement Indarung Port where the 15cm gun was once deployed. On our last day in West Sumatra, we visited Pariaman. We went to see the place where a Japanese Army cannon had been installed, but found it replaced by governmental buildings such as the town hall. Nearby was a concrete bunker topped with a memorial to the citizens of Pariaman and their movement for independence.

The tour group members walked around the Pariaman coast near Pariaman Station (now Pariaman Market). There are still remains of the fort in this area, with its concrete walls reused as fences for the homes of local residents.

At five in the afternoon, we headed for Palembang via Garuda Airline GA031. Palembang is famous as the place where Japanese paratroopers landed.

[Note] During this trip, not a single person discussed their own suffering during the war. They did find the food in Padang a little too spicy, particularly in Nopan and Sawahlunto, where there were no hotels or Chinese restaurants. Goodbye, Padang.

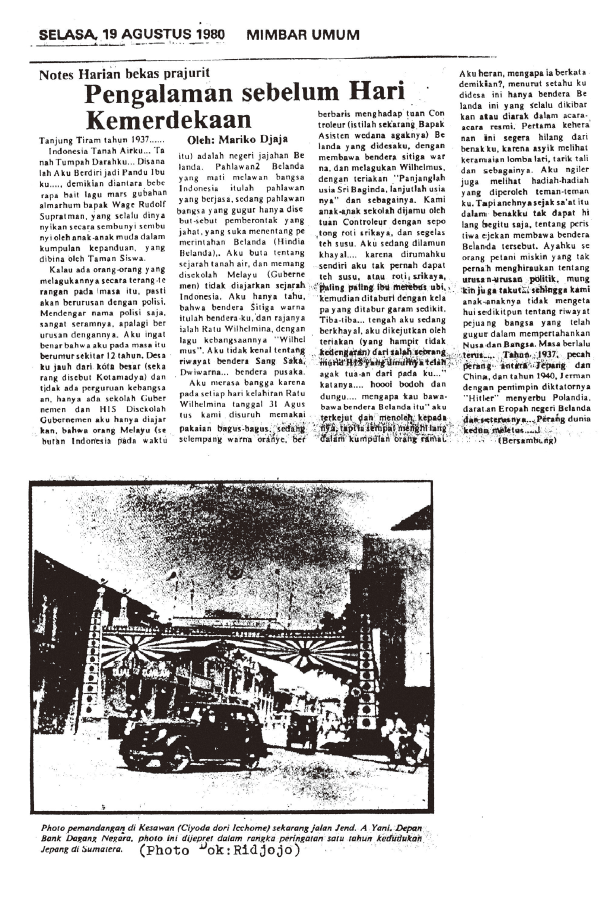

(9) Mimbar Umum (Tuesday, August 19, 1980)

Diary of a Veteran: Experiences Before Independence Day (1)

Mariko Djaya

Tanjung Tiram, 1937.

“Indonesia tanah airku (Indonesia, our homeland) / Tanah tumpah darahku (the land of our birth) / Di sanalah aku berdiri (the place where we stand) / Jadi pandu ibuku (guiding the motherland).” This is part of the national anthem by Wage Rudolf Supratman which youth groups belonging to the Taman Siswa movement would sing in secret.

At the time, singing this song in public would inevitably lead to arrest. The police were a source of fear. When I was twelve or so, I lived in a remote village with no Indonesian public schools, only Dutch colonial schools and HIS (schools for Indonesian nobles). When I studied at the Dutch school, I was brainwashed into believing that the Malays (Indonesians) were colonial subjects of the Netherlands, and the Dutch who fell in the war with Indonesia were the true heroes. The Indonesians who perished were considered simply rebels. I knew nothing about the history of my motherland. At the Dutch school, I never learned anything about Indonesian history. All I knew was that the flag was a tricolor, the Queen was Queen Wilhelmina, and the national anthem was the Wilhelmus. I knew nothing about the red-and-white flag.

On Queen Wilhelmina’s birthday, I wore nice clothes and an orange scarf to line up before the Dutch managers with the other students, waving tricolor flags and singing the Wilhelmus anthem. “Long live the Queen…” and so on. Afterward, the village managers would treat the children to pastries and milk. It was a fancy meal compared to the sweet potatoes with coconut sauce that my mother would make for us.

Daydreaming, I was surprised by an older friend who suddenly addressed me. “What are you doing with that Dutch flag? Stupid!” he said, and vanished immediately into the crowd. I wondered what he meant. The flags raised during events in our village were always the tricolor. However, while I might forget that strange feeling for a while when watching races, tug-of-war contests and so on, I could never really forget what my friend had said about the Dutch flag. My father was a poor farmer with no interest in politics; or perhaps it was out of fear that he never taught his children about the heroes who died for our homeland. In 1937 the Sino-Japanese War broke out, and in 1940 Germany invaded Poland and began its march on Europe. The Second World War had begun.

(10) Mimbar Umum (Wednesday, August 20, 1980)

Diary of a Veteran: Experiences Before Independence Day (2)

Mariko Djaya

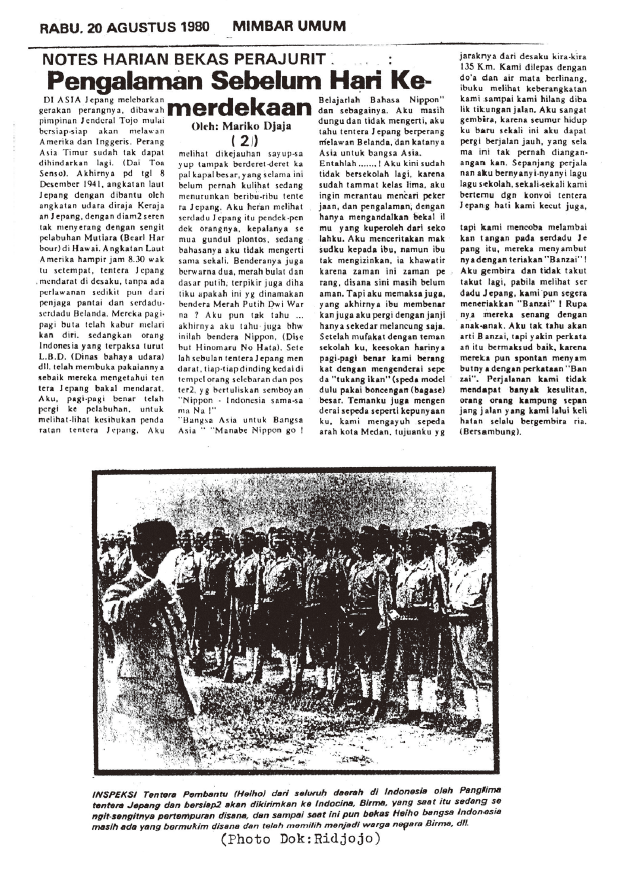

Under General Tojo, the Japanese Army invaded Asia, preparing to fight the British and American forces. There was no way around the Greater East Asia War. On December 8, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Air Force bombed the US Navy base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. At about 8:30 am, the Japanese soldiers made landfall at my village. The Dutch Army and Coast Guard fled straight away, without even trying to resist. The Indonesian militia members learned that the Japanese soldiers had arrived and immediately shed their uniforms.

First thing in the morning, I went to the harbor to see the Japanese soldiers coming ashore. I could see lots of large ships in the distance, disembarking thousands of Japanese soldiers. They were short, with shaved heads, and it seemed strange to me that they spoke a language I couldn’t understand. Their flag was in two colors, a red circle on a white background. Later, I learned that this was the Japanese flag called the Rising Sun. One month after the Japanese soldiers landed, there were posters on every shop wall reading “Nippon-Indonesia sama sama na! (Japan and Indonesia are together),” “For Asia,” “Study Japanese” and so on. I didn’t know anything, but I heard that Japan had come to Indonesia to drive out the Dutch.

I had just finished fifth grade, so I was no longer going to school. I wanted to go to work and make use of what I had learned in school. I talked to my mother about working away from home, but she was too frightened about what might happen to me in the war. Finally I convinced her, on condition that it would be for a short time only. The next day, my mother saw me off as a school friend and I set off on our bicycles to ride the 135 kilometers to Medan. I was happy at the chance to travel further than I ever had before. On the way, we sang songs we had learned in school as we rode along, sometimes passing convoys of Japanese soldiers.

We were afraid of them, but when we waved to them they shouted “Banzai!” in reply. That made me happy, and I wasn’t afraid of them any more. After that, I started saying “Banzai!” whenever I met Japanese soldiers, but I didn’t know what it meant. We had no particular problems on the road to Medan, and the villagers we met on the way also seemed happy.

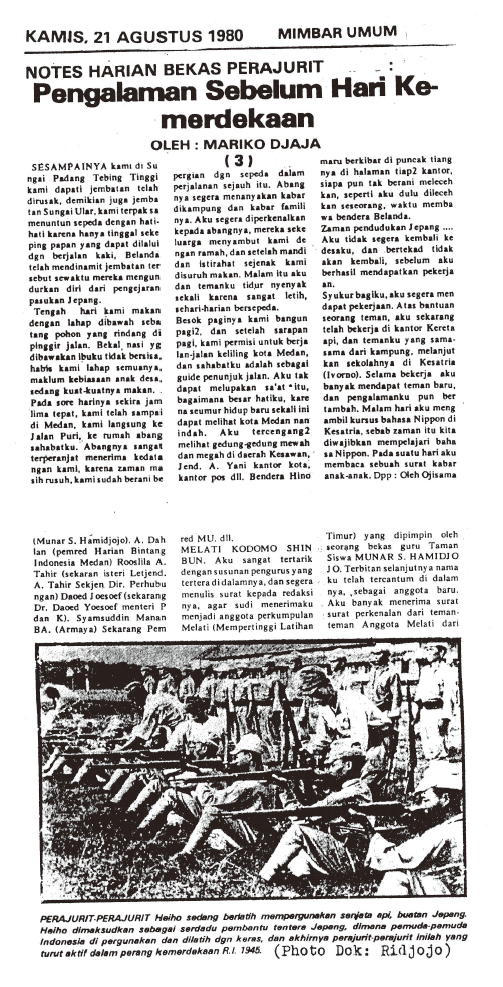

(11) Mimbar Umum (Thursday, August 21, 1980)

Diary of a Veteran: Experiences Before Independence Day (3)

Mariko Djaya

When we reached the Tebing Tinggi river, the bridge had been taken out, so we got off our bikes and pushed them over planks on the broken bridge. The Dutch Army had probably destroyed it to keep the Japanese Army from following them in retreat. We rested under a big tree at the side of the road to eat our lunch. A growing boy, I ate every crumb of the lunch my mother had made for me. At about five in the evening, we reached Medan and went straight to the home of my friend’s older brother on Jalan Puri. He was surprised to see us having come so far on our bicycles in the middle of the confusion. His family welcomed us warmly and gave us a wash, a rest, and a meal. That night I slept very well, exhausted from having cycled all day long.

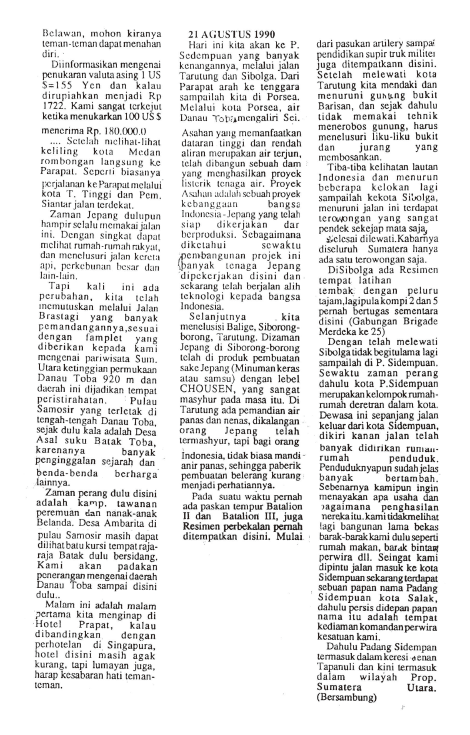

The next morning my friend and I set out for a walk around Medan after breakfast; he showed me around. I will never forget how thrilled I was to see a big city like Medan. The Kesawan district was full of fancy buildings like the provincial capitol and the post office. The Rising Sun flag flew in front of each office. No one could look down on it.

That was the Japanese colonial era. I decided that I wouldn’t go home to my village until I had made it. A friend got me a job with the national railway. Another friend from my village went on to study at a school in Medan. I made more friends and experienced various things. I needed to learn Japanese, so I went to Japanese school at night. One day, I was reading a children’s newspaper. The editors of the newspaper included “Ojiisama” (Munar S. Hamidjojo), A. Dahlan (editor-in-chief of the Bintang Indonesia and Medan Daily News), Rooslila A. Tahir (wife of Lt. General A. Tahir, now head of the Bureau of Transport), Daud Yusuf (now Minister of Education and Culture), Syamsuddin Manan (now editor-in-chief of Mimbar Umum) and more.

This was the Melati Children’s News. I was interested in newspapers, so I wrote to the editorial department and asked if I could join the Melati Association. The Melati Association had been founded by Mr. Hamidjojo, a former Taman Siswa teacher.

The newspaper introduced me as a new member. I received lots of letters from fellow members, not just from Medan but as far off as Kota Raja, Banda Aceh, Palembang, and Lampung. As an active participant in the association, I was popular with the other members.

The Melati News, one of the newspapers officially permitted by the Japanese colonial government, focused on guidance and education for young people in the hope that they would eventually cooperate with the Japanese Army. However, Melati members were actually invoking patriotism and national solidarity in young Indonesians through short stories, poetry, history texts and so on.

In 1944, I began to lose faith in Japanese slogans such as “Let Japan and Indonesia be together,” “Japan is the senior and Indonesia the junior,” “Asia for Asia,” and so on. In reality, Indonesians’ lives were made very difficult. The Japanese had plenty of good food to eat, with no shortages of salt or sugar. The Indonesians, on the other hand, had only corn and sweet potatoes, without even decent clothing. They were also forced to do voluntary duty such as building Japanese forts. Forced to monitor enemy attacks throughout the day and night as laborers, without even sufficient food provided, many Indonesians died of disease. It struck me as extremely unjust.

I was secretly opposed, but I wasn’t strong enough. Without a single weapon to fight with, I knew that going to fight on my own would just be throwing my life away. From that time, I was uncomfortable with working as a civilian, and it was just then that the Japanese Army began recruiting paramilitaries. I left my Melati Association activities behind and began to train under the Japanese Army. I had decided to fight on the front lines, while my Association comrades fought the Japanese Army through the children’s newspaper behind the scenes.

1945, Aceh. I became a soldier. This meant I had to follow the orders of the Japanese Army. I learned battle strategy and how to use various weapons, and was assigned to the Kinomoto unit (artillery). The training to become a soldier was hard, but it was the only way to contribute to my motherland. I was rated higher than my troopmates in all our physical training, and was thus the only Indonesian to be assigned to the Kinomoto unit; all the others were Japanese soldiers. While remaining an Indonesian, I boasted a noble Japanese spirit, easily becoming friends with the others in my unit, where I was well liked. (Brothers on the battlefield are nobler still than brothers by blood!)

Colonel Kinomoto, the unit commander, consistently received good reports of me. One day, I was ordered to report to Colonel Kinomoto. I was in panic, wondering if I had done something wrong, or if my secret thoughts had been discovered. When I arrived at the colonel’s office, Lt. Colonel Yamashita saluted me and showed me into the colonel’s room. I stood in front of him at attention and saluted. He smiled at me, said “At ease,” and began to speak.

(12) Mimbar Umum (Friday, August 22, 1980)

Diary of a Veteran: Experiences Before Independence Day (4)

Mariko Djaya

“Do you know why you’re here?” he asked me. “No, sir,” I said. “Japan has surrendered unconditionally to the Allied forces. This is by order of His Majesty the Emperor, and we must obey. Japanese soldiers have become prisoners of war. With no directions from the Allied Commander, we must maintain the safety of this region,” he explained. “Indonesia is taking steps to transfer its national sovereignty. During the process, to avoid conflicts between Japan and Indonesia, I appoint you interpreter for the Japanese Army,” he said. “Understood, sir,” I said, and returned to the barracks.

In my heart I was cheering loudly. Indonesia was ready for independence. We had waited so long. But it wouldn’t do for me to lose my head and do something careless. My unit retreated from Aceh and moved to the Simalungun region. Instead of training, I was ordered to monitor Japanese soldiers who had committed crimes or tried to escape. The heavy weapons were put away in arsenals, while the cannonballs, hand grenades, bombs and so on were sunk in Lake Toba. I disposed of the weapons within a week. It was hard work, but I enjoyed exploring the area around Lake Toba.

September 1945. When we were deployed to the Simalungun area, the residents had raised bicolor red and white flags, not the Rising Sun. I felt my heart pound at the sight, realizing that Indonesia was independent now. The regulations were strict and it was not easy to leave the base, so I didn’t know what was going on outside. It seemed to be true that we had declared independence on August 17, 1945. However, it was not until September that this information reached the Simalungun district.

The residents heard it on the radio and immediately raised the bicolor flag. The local support troops and military volunteers were disbanded and returned to their homes. Unfortunately, I had not yet been released from my duties, but I thought it would happen soon enough. My duty was to patrol the city of Pematangsiantar at night. The TRI (Republic of Indonesia Army) and militias were assembling at their respective posts. They stood guard with bamboo spears and other weapons.

It was a matter of great pride that Indonesia now had a government and a national army. One day, my comrades seemed to be talking about something very serious. They had been ordered to prepare for a Marpaung unit raid on Japanese army bases, in order to seize their weapons. All the soldiers were forbidden to leave the base. Silently, I tried to figure out whether I could escape from the base that night. The others came to me, saying “You’re the commander’s interpreter!” “You’re his favorite soldier!” and asking me to spare their lives somehow. “When the Indonesian army comes, tell them we’re nice guys and not to kill us!” “If they attack, we’ll give up our weapons instead of fighting back,” they said.

They were no longer willing to fight and had lost all their samurai spirit. They just wanted to get back to Japan safely and see their families. I joked “So you’re all ready to die? Why are you such weaklings all of a sudden? Where’s your Japanese spirit?” “Ridjojo, please help us, we’ll follow your orders!” they answered. To set their minds at ease, I said “We Indonesians won’t kill you. We’ll help you.”

I went on, “Remember the slogan of the Indonesian struggle, ‘merdeka’. When the base is attacked, let’s yell ‘merdeka, merdeka, merdeka!’ to welcome them.” “Yes, all right,” they readily agreed. The cries of “merdeka” actually worked and the Indonesian Army did not fire on the Japanese soldiers; however, the Japanese side handed over all their weapons to the Indonesians. Remembering this later, I smiled to myself. Indonesia was truly independent. Just as in the Youth Pledge of 1928, we were one motherland, one nation, one language.

I was excited that my Japanese troopmates felt the same way as me. I was immediately freed, and my troopmates never opened fire, instead handing their weapons over to the Indonesians. I felt that I had contributed to Indonesia’s struggle.

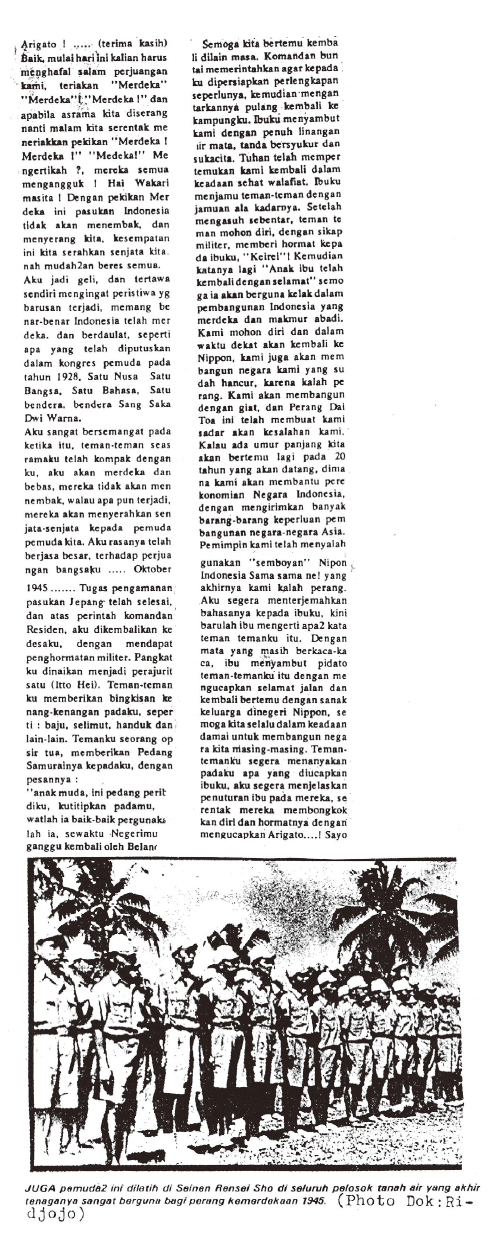

October 1945. My guard duties ended and I was promoted to private first class. This meant I could return home. I received many gifts from my comrades, including clothing, blankets, and towels. One older soldier gave me a sword, saying “Young man, this is for you. Use it carefully.” The commander ordered me to prepare to return home. Several Japanese comrades escorted me to my home in the countryside. My mother wept with joy to see me home again. She thanked God for bringing her child home safe.

Afterward, she served my comrades a meal. After resting a little, they bade her goodbye. “Rise! This mother’s child has come home safely! We pray for the good work he will do from now on in an independent Indonesia. We for our part will return home to Japan and rebuild our country, destroyed by our defeat in war. The Greater East Asia War has brought home to us our mistakes. If we are still alive in 20 years, we will return here and contribute to the development of Indonesia. Our leaders abused the slogan that Japan and Indonesia are together, and in the end they were defeated.” I translated this for my mother. Weeping, she bid them farewell and wished them a safe return to Japan to see their families. My comrades bowed as one, saying “Thank you! Goodbye!”. We shook hands and parted.

(13) Mimbar Umum (Saturday, August 23, 1980)

Diary of a Veteran: Experiences Before Independence Day (End)

Mariko Djaya

November 1945. Because my village is on the coast, I became actively involved along with fellow villagers in leading young people to organize the Indonesian Navy. The navy was essential to protect Indonesia, which had just set foot on the path to independence, from the Allied forces which were looking to recolonize our country. The Dutch Army invaded with the aid of mercenaries, ignoring Indonesian sovereignty. Through negotiations, warfare, guerrilla fighting, and retreat on the part of the Dutch, the Republic of Indonesia was established, but pockets of dissatisfaction remained. The people of Indonesia called as one for the establishment of an Indonesian nation-state, fighting for independence or death.

Finally, Indonesia became an independent nation-state. Indonesians do not resent Japan. Thirty years later, Japan has come back to Indonesia and provided support of various kinds. Through mutual cooperation for the prosperity of the countries of Asia, we can now truly say that Japan and Indonesia are together. Under the Suharto regime, with the Pancasila (Five Principles) and the 1945 Constitution upholding the country, and with the guidance of Allah, I pray that every citizen and region of Indonesia may thrive.

(本文は、2021年7月16日に当サイトにて公開した、伊藤雅俊 史料紹介「日本・インドネシア友好親善永遠の金橋 Jembatan Emas Persahabatan Indonesia Jepang yang Abadi(『報告・論文集』所収)」(史料日本語訳はスヤント氏)の英語版です。)