Machida Yuuichi (Full-time lecturer, Department of Liberal Arts and Basic Sciences, Nihon University College of Industrial Engineering)

Introduction

This paper examines the actuality of the “Southeast Asian fever” prevalent in mainland Japan in the early 1940s, during the Asia-Pacific War (1941–1945), and the role of the media therein, as well as the various motivations of those entering Southeast Asia [1].

As the Sino-Japanese War dragged on, Japan planned its advance into Southeast Asia, signing a friendship treaty with Thailand in June 1940 and invading northern French Indochina in September. In the same month, the Axis was formed, escalating conflict with the Allies (United States, United Kingdom, France, and Netherlands); in July 1941, Japan began its advance to the south, and after the Pearl Harbor attack in December, launched an offensive against US-governed areas in the Philippines as well. The southern advance took Manila in January 1942, Singapore in February, Java in March, and Mandalay in northern Burma in May before slowing down. In terms of Japan’s relationship with Southeast Asia, the treaty of friendship with Thailand was in force, the 14th Army was tasked with the Philippines, the 16th with Java, the 25th with Malaya and Sumatra, the 15th with Burma, and the navy with Celebes and points east [2]. Although Japanese in Southeast Asia had once been few, many military personnel and civilians migrated there during this time.

As the Japanese military moved forward, “Southeast Asian fever” began to sweep Japan. Kozato Akira, a clerk in the Second (and First) Section, Southern Development Bureau, Ministry of Colonial Affairs [3], described “Southeast Asian fever” thus in 1941.

There are now a great number of people inquiring of or visiting our office on a daily basis, either by letter or in person, expressing interest in going to the South Seas. The South Sea fever has spread throughout the prefectures with great vigor as well, with similar inquiries reaching prefectural offices, who then inquire with us as to how to handle them. Recently the radio is chockablock with news of the South Seas, and the newspapers swarm with the southern advance, development in the South Seas, and so on. I believe that the general public has come to feel that they have only to set out for the South Seas on the spot in order to find work [4].

This “Southeast Asian fever” was accompanied by an increase in actual migrants, and the two are thought to be partly connected. According to documents released in 1943 by the Army Press Office, newly arrived Japanese as of December 1942 numbered 6000 to 7000 military personnel and related staff, with similar numbers for those involved in economic development and 3000 returning personnel, showing a steady increase to “more than 40,000 already” by June [5]. This was a sharp increase, given that in 1934 there were approximately 35,000 Japanese citizens in Southeast Asia [6].

Furthermore, according to a survey conducted at the end of World War II by the Ministry of Health and Welfare Repatriation Bureau, as of August 1945 the numbers of military personnel alone were 70,400/1,100 in Burma (army/navy; below likewise), 106,000/1,500 in Thailand, 90,400/7,800 in French Indochina, 84,800/49,900 in Malaya and Singapore, and 97,300/29,900 in the Philippines, as well as some 100,000 civilians [7]. This suggests a sharp increase in Japanese residents in the 1940s. An examination of the meaning of “Southeast Asian fever” at the time must take into consideration this actual social context. In addition, when considering the actual status of migration to Southeast Asia, not only the wartime period but also the construction of postwar relations between Japan and Southeast Asia must be revisited, along with the histories of the people undergoing “back-flow.”

As an overview of the Japanese advance into Southeast Asia at the time, historians Kobayashi Hideo and Nakano Satoshi have discussed the migration of military and construction personnel [8]. However, there has been little research done on how “Southeast Asian fever” was evoked in wartime or how migration from mainland Japan took place.

This paper focuses on media documents in particular to conduct this analysis, for the following reasons. Based on existing histories of Japanese migration, it is well known that various “migrants” traveled to countries throughout the world from the Meiji period. The status of migration based on Japan’s external expansion policies has been clarified with relation to national policy, including examination of economic factors such as poverty deriving from post-Restoration structural inequality leading to overseas labor, or family-based migration through recommendation from family members already overseas. However, there has been little discussion of the role of the media (including newspapers, magazines, overseas travel guides, literature, photography, and film) which directly influenced people with intrinsic motivation to make the trip, as did national propaganda and local circumstances [9]. Actual migration involved various push factors; with attention to the large-scale context of the war and national policy, the information in various media and the direct influence on people who took action must be examined in detail. Residents of urban areas in particular had access to large quantities of information from newspaper and magazine job postings, etc., including malicious scams taking advantage thereof since the Meiji period [10]. Based on these premises, this paper examines the actuality and media landscape of “Southeast Asian fever,” clarifying in what form it was realistically possible.

First, the paper summarizes the situation of “Southeast Asian fever” in wartime and confirms what kind of Japanese people were able to travel there. Second, it discusses aspects of “Southeast Asian fever” and functions of the media by examining relevant articles extracted from databases of the major domestic newspapers of the time, the Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun. Finally, the paper analyzes how career paths to Southeast Asian leadership were selected, drawing on the memoirs of graduates of the Konan Renseiin (Southern Development Training Institute), an educational institution intended to train pioneers in Southeast Asia.

1. “Southeast Asian fever” in the early 1940s

What drew Japanese from the mainland to Southeast Asia at the time? The migration of the military is clearly motivated, but such is not the case for the civilians not dispatched to occupied areas on military duties [11]. In order to explore the existence of various motivations and expectations of diverse people within 1940s Japanese society, let us first examine the aspects of “Southeast Asian fever.”

First, the South Seas Association [12], already responsible for dispatching businessmen, etc., to the South Seas, established a “Southeast Asia Consultation Office” in September 1940 to “provide friendly advice for inquiries such as ‘I’d like to try working in the South Seas’ or ‘What do I need to prepare before I go?’” [13]. There is no material available to suggest what the nature of these consultations may have been. Furthermore, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association, launched in October 1940 as a nationwide citizens’ organization, established a “Greater East Asia Consultation Office” within its Asian Development Bureau in January 1942 to respond to inquiries. Of these inquiries, out of 1022 in total, 913 were in regard to moving to Southeast Asia. Analysis of the article shows that 518 of the requesters were Tokyo residents; 254 were aged between 21 and 30 and 196 between 31 and 40; the most common employment type (148) was mid-sized commerce or industry; 150 had graduated from upper elementary school, and only 36 were university graduates. The Office, currently in the process of selection, would contact “only serious applicants, excluding those chasing money alone” [14]. This suggests that many young people, especially in Tokyo, had hopes for Southeast Asia.

What, then, was the situation on the ground there? As its occupied areas expanded, the Inspectorate General of the military government issued a notice on August 7, 1942, to the effect that “while a comprehensive training and guidance institution for new arrivals in Southeast Asia has been planned via central command and local authorities, special consideration for the importance of Japanese leadership within the military as well is highly desirable” [15]. Given that the shipbuilders already dispatched by the government were “when investigated, only small-time operators with minimal experience who showed up with the shirts on their backs” [16], the expansion of the military government was making personnel difficult to obtain. The directions from the Inspectorate General suggested an urgent need to secure substantial workforce on the ground.

Based on this context, Nanpo no gunsei (Military government in Southeast Asia), published in 1943 by Lt. Colonel Takeda Mitsuji (ed.) of the Army Press Office, stated who was realistically eligible to migrate to Southeast Asia. The book pointed out that “The Yamato people entering the Southeast Asia must bear the burden of their mission of leadership for the peoples governed there, never controlling them with conventional colonialist concepts … The Southeast Asian fever which has thrived among our citizens since the outbreak of war is to be rejoiced at, and while many hope to come to Southeast Asia in order to change or find new employment, based upon the above principles, they must not be allowed to do so. Among them are those who cannot function as essential industrial workers within Japan. For the local region as well as domestically, it is appropriate to provide the personnel necessary for military government and industrial development; the occupations, personnel, etc., truly required and capable of success on the ground are currently under investigation” [17]. The text adds that there are five categories acceptable for relocation: “military government staff,” “military contractors,” “industrial development and trade personnel,” “general entrants,” and “southern advance trainees.”

First, “military government staff” were divided by edict into army chief civil administrators, army civil administrators, army engineers, army attachés, army interpretation officers, army-affiliated civilians, and army interpretation trainees. In addition, there were army temporary workers as well. Interpretation officers, trainees, and interpreters were also directly recruited. “Military contractors” included copyists, typists, grooms, stable hands, waiters, telephone operators, etc. The policy was to employ local people in these positions, but Japanese were also dispatched on site upon recruitment through home duty troops. Applicants were to notify military headquarters or the division command directly, or “inquire with Vocational Guidance Offices, etc.” With regard to “industrial development and trade personnel,” factory management and public transportation operators were designated by the government and contracted by the military. Applicants were required to be employed by the designated companies and to apply to the contracting company suitable for the desired business category via inquiry with the Ministry of Greater East Asia. Finally, “general entrants” were permitted to enter Southeast Asia to the extent their situation required, limited to re-entrants or those who had or had once had trading companies on site, along with their hires as needed. In addition, those trained at the Konan Renseiin and other public- and private-sector training institutes intended to prepare students for Southeast Asia were also expected to enter [18]. In reality, despite the establishment of the military government, the demand on the ground was only for people of this kind.

Thus, “Southeast Asian fever” raged as the Japanese Army invasion proceeded from 1941, with various people hoping to travel to Southeast Asia. However, based on the need for compliance with the wartime regime and demand for local labor, only the five categories of people mentioned above were actually permitted to travel to Southeast Asia.

2. Aspects of “Advice on Southeast Asia” in major newspapers (1): Tokyo Asahi Shimbun “Southeast Asia Q&A”

What, then, was the role played by the media in the rise of “Southeast Asian fever”? Needless to say, newspapers and magazines already had a wide readership at this time; this section examines the possibilities of travel to Southeast Asia in the awareness of Japanese society, with articles in major newspapers as sample material.

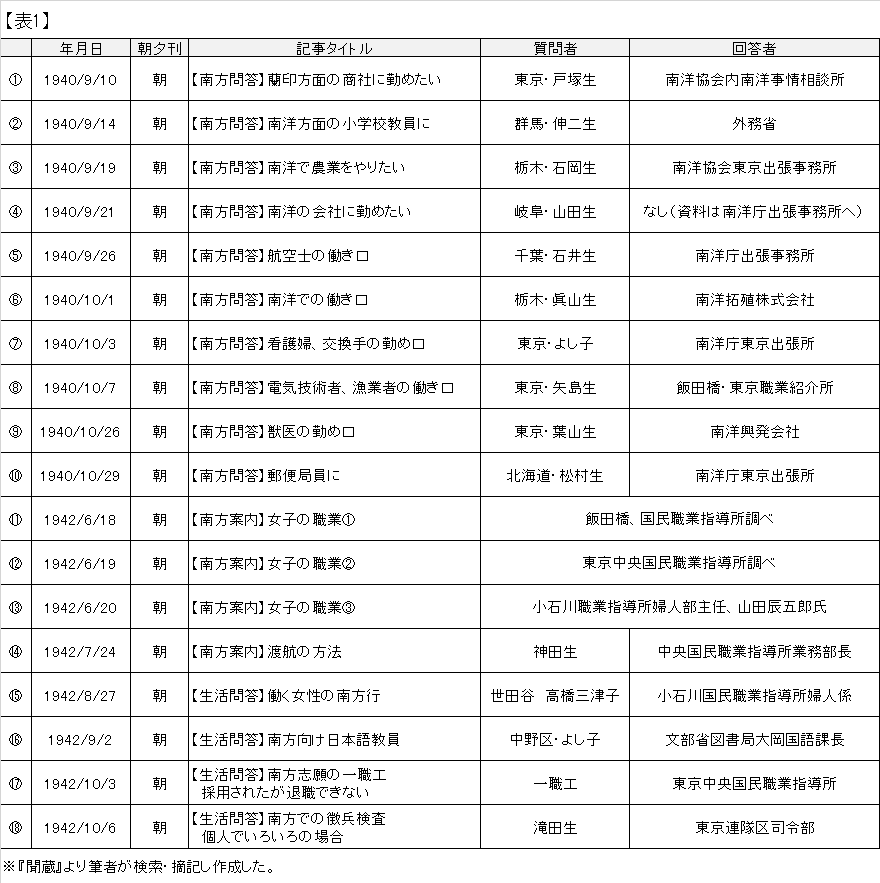

First, let us examine articles on Southeast Asia in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, the first to focus on the region. An overview of the articles is provided in Table 1. These articles were found by using the keywords “Nanpo” (Southeast Asia), “mondo” (Q&A) and “annai” (guide) to search Kikuzo, the Asahi Shimbun database; while other related articles may exist, these are thought to provide an overview of readers’ letters indicating “Southeast Asian fever” and media responses thereto.

Interesting overall trends include the timing. The first wave, from September to the end of October 1940, included ten “Southeast Asia Q&A” items, and the second, from June through October 1942, included four “Guide to Southeast Asia” items and four “Lifestyle Q&A” items. According to these, while there is little material to identify those asking for advice, they mostly came from the Kanto (East Japan) area along with Hokkaido and Gifu; within Kanto, other than Tochigi and Gunma, nearly all were from Tokyo. The content of the questions included consultations on diverse occupations including primary industries, corporations, schools, medicine, engineering, and policing.

Next, a comparison of the responses in 1940 and 1942 shows that the former were nearly all from related agencies or corporations such as the South Seas Association, Territorial Government of the South Seas, or Nantaku (the South Seas Development Company), the latter were mainly from the Vocational Guidance Office, with just a few related responses from the Ministry of Education and the Tokyo Regiment. The South Seas Association and Territorial Government, responsible for introducing immigrants and industry, provided practical responses on the training system, where to send resumes, etc. Conversely, the Vocational Guidance Office (the name given to public employment services in January 1941, handling labor supply creation and personnel sufficiency as the institution in charge of labor mobilization), addressed “not simply employment introductions, but vocational guidance in accordance with the demands of the state. It also provide[d] opportunities for job transfers to owners and employees of overstaffed small to mid-sized businesses” [19]. In short, the responses in the Guide to Southeast Asia treated it as a part of job transfer guidance. However, it should be noted that they handled various wartime issues as well as job transfer guidance, including guidance for those in search of employment in Southeast Asia. With attention to these differences in period and characteristics, let us consider the content.

(1) is a question from a young man considering employment in Southeast Asia after dropping out of a private commercial college. The response is “It is no longer possible to travel there freely from Japan,” informing him that the personnel accessible to trading companies there is restricted and that he should inquire directly with the company or visit the South Seas Consultation Office within the South Seas Association in Marunouchi.

(2) is in regard to procedures and salaries for elementary school teachers. The response of the Territorial Government’s branch office was that about 30 people out of 150 applicants were hired yearly, restricted to couples in which only the husband was a teacher, paid 65 yen or less, with few school-aged children, and “depending on individual effort”; hiring took place every February based on applications to the branch office, and hiring as a junior official would entail payment of 110% domestic salary plus 10 yen and a 1/2 or 2/3 bonus. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded that, through applications from local Japanese Associations to overseas designated elementary schools, recommendations of suitable applicants were requested from regional officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or Ministry of Education, and that inquiries should be made to the American and European Bureau or East Asian Bureau.

(3) is a question from a 28-year-old man from a farming village, a graduate of a 4-year agricultural school. The Territorial Government Tokyo branch office responded that they recommended going elsewhere than the Dutch East Indies or Philippines, introduced their suggested locations, informed him that success after three years would result in aid and that the required qualifications were to be between 20 and 55 years old, married, with agricultural experience, and told him to inquire for details.

(4) is a question from a 19-year-old agricultural school graduate. The Territorial Government responded that the Tropical Industry Research Laboratory on Palau was recruiting pioneer trainees, that graduates could be employed by the Territorial Government or the Development Company with a salary of 65 yen, and to consult the Territorial Government Tokyo branch office for application regulations.

(5) is a request for work as flight crew by a person with second-class piloting and third-class radio operator qualifications. Imperial Japanese Airways responded that they mainly hired first-class pilots and radio operators, while second-class radio operators could be hired as ground staff in the South Seas Islands and that the salaries were in the range of 40 to 50 yen. The Territorial Government responded likewise that hiring of communications officers was irregular and dependent on vacancies, that the applicant should send in a resume, and that salaries were 38 to 45 yen.

(6) is a question about “suitable employment opportunities” from an 18-year-old elementary school graduate from a farming village. The Development Company responded that the Philippines and Dutch East Indies were “difficult” for agricultural immigrants, that a 50-person pioneering business was planned for the Yap Islands in accordance with the development of directly managed farms in the outer South Seas such as Borneo and the Philippines, and that trainees were to be farmers aged 21 to 27 who would receive salaries of 50 yen during training. They added that phosphate mining was taking place on Angaur Island, involving many Okinawans, at day rates of 1.7 to 2 yen.

(7) comprises two inquiries about procedures and salaries for nurses, midwives, and telephone operators. The Territorial Government Tokyo branch office responded that “there appear to be no vacancies at the moment” and suggested that applicants submit their resumes directly to local hospitals, while answering the second inquiry with “hiring is handled locally,” but not to expect much as “there are few openings.”

(8) comprises two inquiries about employment opportunities from an electrician and a fisher. To the former, the South Seas Electrical Company responded that there was an electrical station hiring in their territory of Koror, offering 1.6 times Tokyo salaries, but that the “Employment Restriction Ordinance” was applicable and to inquire. To the latter, the Iidabashi Tokyo Vocational Guidance Center responded that there was no recruitment for odd jobs and “no current recruitment for major fisheries,” advising the fisher to apply to any Vocational Guidance Center with regard to Nippon Suisan, Nanko Suisan, or Borneo Suisan. In addition, (9) is a question from a prospective veterinary school graduate, with the response of “no vacancies at this time” and a mention of future hiring needs. (10) is a question from a postal clerk hoping to work at a Southeast Asian post office, to which the Territorial Government Tokyo branch office responded “The state of vacancies is not clear at this time; applicants should send their resumes,” and stated the salary. The questions and answers give a sense of local labor demand at the time.

The following (11) through (13) are not letters with questions but columns from the Koishikawa Vocational Guidance Center (by Yamada Tatsugoro, head of the Women’s Division). They are thought to be responses reflecting a rise in inquiries.

(11) includes recruitment guidelines for the first arrivals in Shonanto (Singapore), as “based on job postings from the local setting, becoming a military-affiliated civilian is the only way to go,” an option which “is expected to increase in the future.” Typists were to be graduates or equivalent of girls’ schools or girls’ commercial schools with at least one year of work experience, aged 18 to 25 and paid about 3 yen a day; announcers were to be aged 20 to 30, graduates of vocational schools, women’s colleges, or higher, with good English and paid 150 yen initially; nurses were to be aged 18 to 30 with regular nursing qualifications, paid 75 yen monthly; clerks “ha[d] not yet been recruited in Southeast Asia,” but based on Chinese practices were to be aged 18 to 25, graduates of girls’ schools or girls’ commercial schools, and paid 60 to 70 yen.

(12) is an explanation of recruitment methods. When recruiting large numbers, newspaper ads were used; for smaller numbers, recommendations were made from applicants’ registration for employment, with examinations determining hiring. Registering for employment at the Koishikawa Vocational Guidance Center Women’s Division required no preexisting health conditions and parents’ approval, as well as submission of a consent form, health check form, family register copy, and identification from a municipal head. (13) is a list of guidelines upon employment. First, those hired locally would become “military-affiliated civilians, with an arrival bonus paid, travel fees not required, and food, clothing, and shelter provided. The period of employment was two years or more; permanent residency was possible upon contract termination, but becoming a military-affiliated civilian required “a strict awareness of the situation,” prohibiting “the intent just to earn money or to see the sights.” Furthermore, employees of munition factories and military construction sites at this time were asked to “refrain [from leaving] due to labor shortages.”

(14) is another response to questions. In response to a request for instructions on how an “industrial warrior” could travel to Southeast Asia, the response was that “as individual free travel is not yet permissible, the only way is to become a civilian affiliated to the local troops.” The advice was to inform the “duty section” of the nearest of 13 Vocational Guidance Centers of an interest in Southeast Asia and to register as an applicant for a military-affiliated civilian position with a resume. Thereafter, salaries, etc., were noted as above.

(15) is another response from the Vocational Guidance Center to a questioner wanting to work as a typist in Southeast Asia, with instructions to register at a Vocational Guidance Center and relevant precautions: travel would be as a military-affiliated civilian, the term was two years, applicants must have graduated from a girls’ high school and must be single, the salary was 80 yen, and telephone operators and clerks were currently being recruited for Southeast Asia and the Kwantung Army. As for the resumes submitted by these applicants for Southeast Asia, an article on August 5 notes reports that the Tokyo Central Vocational Guidance Center in Iidabashi had “a two-foot pile of candidate resumes, too many to count but surely numbering in the thousands,” with many hoping to be drafted for civilian work after failing the military draft, and others signing in blood [20].

(16) was a question regarding the Ministry of Education’s lecture course for teachers of Japanese in Southeast Asia, with the Ministry’s Library Bureau responding that it would be held for three months from October 1942, for graduates of secondary schools or vocational schools, or equivalent, with tentative plans to hire 500 people.

(17) was from a laborer who had wanted to travel to Southeast Asia but had not been granted permission to leave the current job. The Vocational Guidance Center responded that at a designated factory under the Ordinance on Labor Arrangements, “leaving requires permission” and that the writer should consult with the factory chief in order to receive permission to leave, or else visit a Vocational Guidance Center consultation office. (18) was a question about whether the military draft exam could be taken in Southeast Asia if arriving there before undergoing the draft. The response was that under the Draft Law, enlistment could be postponed until age 37, followed by transfer to civilian military service.

Examining the characteristics of these articles, we find that the responses in the post-September 1940 “Southeast Asia Q&A” were in regard to various occupations. In terms of actual work through the Territorial Government or South Seas Association, the latent potential was noted while increasingly tending toward advice to consider migration as a “military-affiliated civilian” through the Vocational Guidance Centers, from the perspective of the draft as well as job transfer guidance. From 1942, the possibilities for women’s labor were pointed out in particular, while the actual indication was to travel as a “military-affiliated civilian.” The Q&As in these articles ended up providing specific procedures in response to diverse manifestations of “Southeast Asian fever,” while also having a “cooling” effect due to their presentation of a harsh reality.

3. Aspects of “Advice on Southeast Asia” in major newspapers (2): Yomiuri Shimbun “Advice on Southeast Asia”

Next is the Yomiuri Shimbun’s “Advice on Southeast Asia.” Table 2 shows the search results from Yomidas, the newspaper’s search engine, for the keywords Nanpo (Southeast Asia), mondo (Q&A), and annai (guide). While other related articles may also exist, an overview can be gleaned from these in terms of the exchange of letters and responses with readers. As far as can be observed, there were 12 “Advice on Southeast Asia” items from late 1941 through 1942, as well as two items with clear answers in the “Newspaper Advice” format. Based on these items, although there is little material to identify the original writers, they too were mostly located in Tokyo (other than Shizuoka and Yamaguchi), and were concerned with a wide variety of occupations, including interpretation, primary industries, leadership, policing, and military affiliation.

It seems that the reporter in charge consulted with the relevant authorities depending on the request for advice; the latter half is notably nearly all responses from the Koishikawa Vocational Guidance Center and the reporter. Like those in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun above, this is thought to be due to the worsening war situation as well as a growing feeling that “Southeast Asian fever” should be handled through the state vocational guidance system.

(1) is a question on how to enter the Southeast Asia Pioneer Training School run by the Governor-General of Taiwan. The response was that there were A and B classes of entry with a December 10 deadline, with trainees sent to South China and the South Seas after a year of training. The writer was directed to apply to the Japan Youth Association in Azabu Ward, Tokyo, for domestic recruitment.

(2) was a question about working in Southeast Asia in the future. The response pointed out that some 70 million people in Southeast Asia used Bahasa Melayu and that its fundamentals could be mastered in three months of practice; along with information on the Tokyo and Osaka Schools of Foreign Language and various reference books, the response noted that “it is important for us, as leaders, to adequately master the languages of Southeast Asia.”

(3) is a question about working in Borneo “if given an opportunity in the future.” The response was that opportunities were limited to Northern Borneo and that while agriculture there was thriving, it was not easy for a man alone to travel there to work and marriage was a requirement. The response also touched on “setting a good example for the Malay” and “serving as a good admonition against their polygyny.”

(4) is a direct question about joining construction troops in the South Seas. The response was that carpenters, plasterers, clerks, etc., were “being hired as military-affiliated civilians through guidance centers,” with “hiring assignments provided in case of vacancies.”

(5) is a question about where and how to find work. The response was that “it is not permitted to travel individually and begin an independent business,” with an introduction to the South Seas Association’s commercial trainee program.

(6) is a question about how to find work as a farmer in the Philippines. The response was that while “there seem to be no agents currently handling agricultural transfers to the Philippines … this is because it is our mission to guide the local residents in dramatic improvements of Southeast Asian agriculture based on the superb Japanese intellect, technology, and capital.” It was also noted that a few experimental transfers were being permitted through the Taiwan Governor-General Industry Bureau Agricultural Section.

(7) is a rather unexpected question suggesting that local processing of katsuobushi bonito flakes should be under consideration. The abstract response was that “the mission left to us, untouched by America or Britain, is the pioneering of Southeast Asian fisheries.”

(8) is a question from a junior high school student about guidance centers for Southeast Asian development; the Takunanjuku responded with its entrance qualifications, deadlines, and application methods. (9) is a question about the languages required to work in Burma. The Japan–Burma Association responded that it was “a shame” that no scholarly books were available in Japanese, that the local residents were studying literacy and English, and that it was possible to master the rudiments of Burmese in three months.

(10) is a question from a woman studying home economics at a vocational school on whether there were agents who could matchmake her with a man working in Southeast Asia. The Overseas Women’s Association responded that there had been 15 or 16 successful couples and that efforts were on hold during the war, but “applications [we]re accepted”; however, “selection is more stringent than within Japan, and excellent brides are a must,” so they must “understand the local situation and context thoroughly, bear in mind their leadership position as Japanese women, and be effective as angels of the house,” understanding Southeast Asian affairs thoroughly. Furthermore, the morning edition of August 18, 1942 carried an article on page 4 titled “The Advance of the Marriage Bureau” with regard to marriages overseas. The article introduces the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s establishment of a marriage report conference and its consultations. Yasui Hiroshi, Director of the Ministry’s Eugenic Marriage Consultation Office, stated that the difficulty of marriage domestically and overseas must be handled, and that as a policy to resolve the issue of “unnatural singlehood,” they were contacting organizations of Japanese resident overseas, opening marriage guidance centers throughout the country, and “expanding continental brides … throughout Greater East Asia” [21]. The existence of plans like these, making use of “Southeast Asian fever,” must not be overlooked.

(11) is a police constable hoping to work at a Southeast Asian consulate; the response was that “at this time, there is no process for application.” (12) is a question from a junior high school graduate about the Eastern Occupational Training Center and employment in Southeast Asia. The response was a stern note that “dreams of getting rich quick in the new world of the South Seas are not to be tolerated” and that the Training Center would enable consultation with a guidance center. The response added that currently there were vacancies in Southeast Asia, with food, shelter, and clothing provided, for copyists (110 yen), typists (75 yen for Japanese, 100 yen for European languages), clerks (140 yen), messengers (90 yen), interpreters (150 yen), etc., and that “trading company vacancies are also expected to increase.” Age limits applied, generally up to age 45. This was a practical response from the director of the Vocational Guidance Center vacancy section.

(13) is a question about working in Southeast Asia as a military-affiliated civilian; the response was that the wide range of occupations included carpenters, plasterers, and odd-job workers as well as clerks and interpreters, for one- or two-year terms. The response noted that the many “thoughtless” applicants such as those hoping to make their fortunes were discarded during the hiring process, that “only those prepared to dedicate themselves to the same degree as the military” were hired, and that the Vocational Guidance Centers at Motomachi, Hongo Ward and Koishikawa, Koishikawa Ward in Tokyo were recruiting physical laborers as military-affiliated civilians.

(14) and the following items are questions concerning women. (14) is a question from a woman hoping to work in Southeast Asia or on the Continent. The Vocational Guidance Center Women’s Section responded that “becoming a military-affiliated civilian [was] required,” and that the only way was to apply for vacant typist, clerk, telephone operator, or nurse positions recruited by the military through the Vocational Guidance Centers, etc. (15) is a question from a girls’ high school graduate hoping to work as a military-affiliated civilian in Southeast Asia. The response recommended that she register with a Vocational Guidance Center. (16) is a question from a woman hoping to work in Southeast Asia after qualifying as a Japanese-language typist, with a response introducing the Women’s Section of the Central Association of Overseas Landsmen.

(17) is a recommendation of the Southeast Asia Consultation Office in Kojimachi. This office was run by the City of Tokyo; according to another article, the Southeast Asia Consultation Office, founded jointly by the former prefecture, city, and Chamber of Commerce of Tokyo, was expanded in April 1943 and “began proactive activities,” open to ordinary citizens. Specialists handled the consultations, including Tokyo Imperial University Professors Hayashi Hiroshi and Miura Ihachiro (forestry and fisheries), Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce Geological Survey Office Director Yamane Shinji (mining), former East India Nippo president Saito Masao (crafts), former Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce Saigon correspondent Kato Toshio (French Indochina), former Bangkok Trade Agency director Oyama Shuzo (Thailand), former South Seas Association Singapore Product Exhibition Hall director Matsukawa Shozo (Malaya), Nippon Suido President Fukushima Hiroshi (Burma), Army Ministry contractor Takei Juro (East Indies), and South Seas Economic Research Institute contractor Miyoshi Tomokazu (Philippines) [22].

Thus, the responses from relevant authorities regarding future travel in the Yomiuri Shimbun’s advice column emphasize “leadership” on the ground, while providing realistic responses linked to travel policy, without fanning the flames of “Southeast Asian fever.” Auxiliary organizations such as the South Seas Association responded to requests for advice through 1941. From 1942, as labor shortages arose, a more positive view of travel to Southeast Asia emerged (excluding the transfer of excess labor and vocational guidance). The potential for women to become “brides in Southeast Asia” also arose. Thus, the predicted situation in which “Southeast Asian fever” would lead to a mass migration of workforce was not necessarily desirable in terms both of execution of labor mobilization plans and of demand and supply on the ground; these newspaper articles performed the function of “cooling” readers by informing them of the realistic difficulties involved, as well as guidance for migration within a scope congruent with the wartime situation.

4. The context of “Southeast Asian fever” within the Konan Renseiin

What were the causes of “Southeast Asian fever”? This section examines this question with reference to the actual status of training institutions pointed out in the text by the Army Press Office mentioned above. The use of memoirs by individuals may provide a glimpse of the diverse factors behind the people determined to move to Southeast Asia.

Training institutes for foreign action included Koa Kunrenjo (Asian Development Training Institute), established in the early 1940s for local residents [23], the Koa Renseiin (Asian Development Training Institute), established by the Koain (East Asia Development Board) for personnel involved in Chinese politics, economics, and culture, the Southeast Asian Farmers’ Training Organization led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry [24], etc.; the Konan Renseiin, or the Southern Development Training Institute, was established to train personnel for Southeast Asia. First, let us conduct an overview of the institute using extant research.

The Konan Renseiin was a state institution under the auspices of the Ministry of Greater East Asia, intended to train personnel for Southeast Asia. Before its establishment, bureaucrats from each Ministry had taken part in Southeast Asian occupied territory administration along with civilians, as South Seas personnel (administrative personnel): administrative directors, attachés, engineers, etc. The institute was established so that they could be trained before going to the occupied territories. Konan Renseiin graduates comprised part of the entrants to the region, particularly administrative personnel for Southeast Asia. Thereafter, the organization was renamed Daitoa Renseiin (Greater East Asia Training Institute). According to Ota Koki’s introduction to the establishment process, the organization was an overall training institution for bureaucrats and civilians who would be involved in administration of the occupied territories [25]. The institute’s organizational structure was rather complex. Here, reference is made to the overview in Takunanjuku-shi: Takunanjuku Daitoa Renseiin no kiroku (History of the Southern Development Seminar: Records of the Southern Development Seminar Daitoa Renseiin), Seikei Shinsha, 1978. This book is the only document edited by Renseiin graduates and serves as a basic source. The overview below draws on Maruyama Noboru’s “Konan Renseiin/Daitoa Renseiin” in this volume; for the 3rd, 4th, and 5th graduating classes, figures regarding language education are drawn from Matsunaga Noriko’s recent “Soryokusen” ka no jinzai yosei to Nihongo kyoiku (Personnel training and Japanese-language education during the “all-out war”), 2008.

The Konan Renseiin was first established in November 1942. It was divided into a Main Department, First, Second, and Third Departments, and Research Department. The First Department was a three-month training course for those assigned as army and navy administrators in chief, and no longer existed from the second graduating class. The Second Department was a six-month course for publicly recruited graduates of higher technical schools and universities. The first graduating class produced many personnel for Southeast Asian military governments and corporations on the war front, whereas the third class were deployed to Manchuria and faced defeat in the war. The Third Department was the successor to the Takunanjuku (Southern Development Seminar), an auxiliary organization of the Ministry of Colonial Affairs, transferred in January 1943. Its second cohort of students graduated early, in July, to be sent out into the field, with the third cohort entering in May 1943.

Thereafter, in November 1943, the Konan Renseiin and Koa Renseiin were merged into the Daitoa Renseiin. The first students of the Daitoa Renseiin were thus actually the fourth graduating class. In the reorganization, the Third Department became a three-year program, the Konan Renseiin First Department was abolished and the existing Koa Renseisho took its place, while the Research Department remained.

The third graduating class were to finish early and be sent to Southeast Asia. However, the state of the war had already worsened for Japan, and dispatch to Southeast Asia was unrealistic for most of them, who instead went on to military academies, etc. Graduates in the fourth cohort were dispatched only to North China (149 people) and Mongolia (30 people), as Japan had already lost control of Southeast Asian waters. The fifth and last class were in their fourth month of training when the war ended. While still considered a training organization for Southeast Asia, the institute was almost entirely unable to fulfill its mission from the Daitoa Renseiin period.

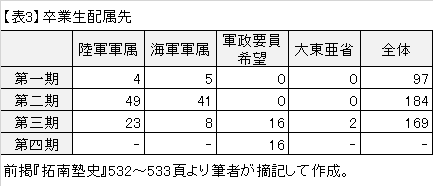

The graduates’ assignments, as seen in Table 3, show the changes over this period clearly. The first graduating class was composed of 97 students, the second of 184, and the third of 169. There were 169 graduates in the fourth class; however, while the 12 army enlistees and four navy enlistees shown in the table applied for military government positions, 149 students (not shown) were assigned to a Tianjin warlord-owned munitions plant and 20 to the Mongolian government. Graduates were active in Southeast Asia only up through the third graduating class, and civilian careers were considered important as well as the military.

Although Matsunaga (op. cit.) discusses the training content in Chapters 1 and 2, she dwells only on the actual language education and does not analyze the graduates themselves. Therefore, an analysis of the background of the Southeast Asia dispatch and its subjects’ characteristics is required, building on Matsunaga’s basic figures and with assistance from their own memoirs. Graduates of the Second and Third Departments are the subjects of the analysis, focusing in particular on the first through fourth graduating classes. The Takunanshi-juku document mentioned above contains contributions from 209 students, instructors, and others. Of these, 135 recall their time as students. Their writings have been thoroughly surveyed, and excerpts grouped by cohort of enrollment are included below.

First, let us examine the motivations for enrollment in the Second Department. First is Kusunoki Masazumi, a member of the first graduating class in the Second Department: “Signatures on the Rising Sun Flag.”

In August of Showa 18 [1943], I left the ivory tower where I had been working as a university lecturer to follow the army out of the motherland as an Army bureaucrat with the 25th Army Inspectorate [26].

This unusual case is an example of a former academic researcher.

Next is Fukui Genji of the same class: “The Renseiin and Me.” After entering the 34th Shizuoka Infantry Regiment, Fukui was discharged due to injury and became a teacher at the fishery school in his hometown.

I felt I had to escape the draft; at that moment, the gods smiled on me and held out a rescuing hand. I came across a newspaper article titled “Go South, Young Men: Konan Renseiin Recruits Students.” My mind was made up instantly, with no hesitation. I knew they would be flooded with applicants from universities and higher technical schools, but my only option was the Renseiin. Being drafted again would mean my death [27].

While the two examples are in contrast, they indicate that students included those who fled the “ivory tower” to make the leap to Southeast Asia as well as those who, spurred by a newspaper article, chose to head to Southeast Asia in order to avoid a second draft.

Next is Ueda Jun of the second graduating class: “Memories of the Entrance Exam.”

Near the end of my fourth year at a commercial school (old format), I began to take an interest in my future. Even if I wanted to go on studying, at the time there were few paths to higher education from vocational schools. Still, especially as my grades were quite good, I found it hard to give up my ambitions for further study. However, I had lost my father in youth and my two older brothers were then serving in the army. It would have been impossible for our family to come up with my school fees. Still, I kept looking among school guides for an inexpensive option. … I discovered the Takunanjuku just days before the application deadline. It suited my longing for the colonies, the costs were low, so I decided on my own that this was it for me and set off to the photographer’s at once [28].

Ueda’s memoir suggests a substitute for “higher education fever” in the context of a longing for the colonies.

Next we have Morinaga Tsukasa of the third graduating class in the Second Department: “The Greater East Asia Cram School.”

The third class was made up of students at least five years out of university or higher technical school, some with experience in the colonies or the army, others who had found their way here from life as employees of civilian companies; assembled through a remarkable selection process, they were people who had earned trust and rank in their fields and should have been of central importance [29].

According to Morinaga, the third graduating class was characterized by many members with corporate or military experience. In other words, there were more than a few people who were willing to abandon their careers and fling themselves into Southeast Asia.

Then there is Takahashi Nobuo of the fourth graduating class: “Nibbling the Palmyra Trees.”

I learned about the Takunanjuku in chemistry class during my fourth year of junior high school. The teacher, Professor Suzuki, read out a letter from Kumojima, who was a year ahead of us (in the third graduating class). It explained what the school was like, said it was publicly funded, and urged him to have younger students attend. With the war in a state of emergency, I had been worrying about what to do with myself after graduation, and decided on the spot to take the exam. My parents agreed as well [30].

In this case, the presence of a senior student and the guidance of a teacher affected the writer’s post-graduation path.

Finally we have Hirao Kazuo of the fourth graduating class, who described a similar situation in “The Daitoa Renseiin Third Department and Me.”

Unable to defy my parents’ prohibition on studying the humanities, I took the exam for the local Eighth High School science course and flunked spectacularly. That was when I saw an article in the exam magazine Keisetsu Jidai by Tanaka Shigeyoshi of the third graduating class, another Aichi man, about life at the Renseiin. This is it! I thought in triumph. [31]

This indicates that two members of the fourth graduating class, struggling with career plans, learned of the school and were motivated to enroll by older students from their home region, whether at school or through a magazine. Overall, the Renseiin formed a career path for these young men struggling academically or economically, due not only to a sense of mission toward Southeast Asia but also a longing for the colonies, a desire to escape the draft, or a passion for higher education.

Based on the memoirs above, the military-affiliated civilian designation among those traveling to Southeast Asia covered a wide range of people; the memoirs of Koa Renseiin students, expected to contribute to the development of Southeast Asia per the national strategy, indicate that as well as a source of pure hope for Southeast Asian development, this was also an effective career path for young men in need of escaping the draft or unable to pursue higher education for academic or economic reasons. In short, travel to Southeast Asia presented itself as an immensely attractive option within the context of wartime claustrophobia, blocked career paths, and the creation of a longing for the region in the sense of a suitable response to young people’s unattainable desires for upward mobility or the search for something missing.

Summary

The above discussion is summarized as follows. First, “Southeast Asian fever” was on the rise in the early 1940s, with many inquiries to relevant ministries and agencies. Based thereon, consultation offices were established by the South Seas Association, Imperial Rule Assistance Association, etc.; however, in reality, free travel was not permitted and it was confirmed that the only options were to be assigned as a “military-affiliated civilian” or to travel on business as a company employee. Second, responses to readers’ letters to major newspapers motivated by “Southeast Asian fever” included specific possibilities regarding travel to Southeast Asia. At first, most responses were from the South Seas Association and South Seas Territorial Government. However, from 1942, in accordance with wartime mobilization, responses were observed in which Vocational Guidance Centers noted the possibility of military affiliation for registrants. In 1943, a Tokyo prefectural consultation office handled these issues as well, with expectations for “brides in Southeast Asia” arising as well.

Third, the memoirs of students at the Konan Renseiin, expected to become core leaders of Southeast Asia, were examined to illustrate the various forms of “Southeast Asian fever” and what paths they took as leaders after graduation. The examination found that “Southeast Asian fever” was present not only in those hoping to travel to Southeast Asia based on experience as working adults, but also in the expectations of those escaping the draft or unable to pursue higher education; although some were dispatched there, as the wartime situation worsened, the school was unable to produce leaders for Southeast Asia in large numbers.

Thus, “Southeast Asian fever” thrived in response to Japan’s military expansion in the early 1940s; in reality, however, for many hopeful travelers the only way to get there was through “military affiliation” via corporations or Vocational Guidance Centers, while those hoping to become leaders chose career paths through various public training institutes such as the Takunanjuku.

Tasks for future research include an examination of those who actually traveled to Southeast Asia up until the end of the war, “Advice on Southeast Asia” in other newspapers, and the activities of the people and organizations responsible for shaping “Southeast Asian fever” in textual media. Regarding textual media, an examination of Mihira Masaharu (also known as Mihira Seido) is currently planned. During the war, Mihira established the so-called Greater Japan Overseas Youth Association, publishing many foreign guidebooks; after the war, he opened the marriage agency Kibosha in response to the difficulties of war widows and demobilized soldiers in finding marriage partners. He also established the Japan Overseas Immigrants’ Association, similar to its prewar version, and published guidebooks on overseas immigration. Today, he has been almost completely forgotten. The examination of Mihira is expected to shed light on the diverse people and media involved in “Southeast Asian fever” from an unprecedented angle, clarifying how the longing for foreign lands created by such people, along with its alignment with wartime and postwar experiences, formed the historical context for the “back-flow” migration boom in postwar Japanese society from the 1950s.

Notes

[1] Nanpo (Southeast Asia, or “the South”) and Nanyo (South Seas) are not precise geographical terms, but general expressions covering the regions from India to Southeast Asia, sometimes even including Australia and New Zealand. Despite these complexities, this paper uses the term “Southeast Asia” for consistency as a translation of Nanpo. Under military government, Nanpo was a general term for modern-day Southeast Asia, the Central Pacific, and New Guinea; when the Solomon Islands and eastern New Guinea became known as the “Southeast,” Southeast Asia was often called the “Southwest” (Center for Military History, National Institute for Defense Studies, National Defense Agency ed., Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei (Historical documents: Military government in Southeast Asia), “Commentary,” Asagumo Shimbunsha, 1985, p. 13).

[2] The army was in charge of Hong Kong, the Philippines, British Malaya, Sumatra, Java, British Borneo, and Burma. The navy was in charge of Dutch Borneo, Celebes, the Moluccas, the Lesser Sunda Islands, New Guinea, the Bismarck Islands, and Guam. As the occupied territories expanded, navy territories increased while army territories gradually decreased as Burma and the Philippines became independent (Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei op.cit., p. 13).

[3] Clerical Section, Secretariat of the Minister of Colonial Affairs, ed. Takumusho shokuinroku: Showa 16-nen 8-gatsu 1-nichi genzai (Staff list of the Ministry of Colonial Affairs: As of August 1, 1941), Clerical Section, Secretariat of the Minister of Colonial Affairs, 1941, p. 80.

[4] “Special program: Discussion on what we want to learn and talk about in Southeast Asia, a new venue for the development of our people,” in Tokyo-shi Sango Jiho (Tokyo City Industry Times) Vol. 7 No. 3, March 1941, p. 40.

[5] Lt. Colonel Takeda Mitsuji (ed.), Nanpo no gunsei (Military government in Southeast Asia), Army Press Office, 1943 (first edition). “Part 4: Southeast Asia dispatch of military government personnel and related trading companies and the early military government structure,” in Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei op. cit., p. 183.

[6] Irie Toraji, Hojin kaigai hattenshi (History of Japanese development overseas), Ida Shoten, 1942, pp. 408–409. Based on a Ministry of Colonial Affairs survey.

[7] Japanese Association for Migration Studies ed., Nihonjin to kaigai iju: Imin no rekishi/genjo/tenbo (The Japanese and overseas movement: The history, current status, and prospects of migrants), Akashi Shoten, 2018, pp. 206–209.

[8] Kobayashi Hideo, “Romu doin seisaku no tenkai” (Development of labor mobilization policies) in Hikita Yasuyuki ed. “Nanpo kyoeiken” (The “Southeast Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”), Taga Shuppan, 1995, chap. 12; Nakano Satoshi, Tonan Asia senryo to Nihonjin: Teikoku Nippon no kaitai (Southeast Asia’s occupation and the Japanese: Dismantling Imperial Japan), Iwanami Shoten, 2012, p. 29.

[9] In terms of literature, the influence of writers drafted to work in Southeast Asia cannot be ignored. See Sokolova-Yamashita Kiyomi, “Nihon gunseika Indonesia ni okeru Hayashi Fumiko no bunka kosaku” (Hayashi Fumiko’s cultural operation in Indonesia under the Japanese military) in Nihon Daigaku Geijutsu Gakubu Kiyo (Research in Arts, College of Art, Nihon University) Vol. 68, 2018, etc. In terms of travel guides, Mihira Masaharu’s Kyoeiken hatten annaisho (Guide to the development of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, Greater Japan Overseas Youth Association, 1944) is introduced in Hayakawa Tadanori, “Nihon sugoi” no dystopia: Senjika jigajisan no keifu (The dystopia of “Japan Is Great”: The genealogy of singing one’s own praises in wartime), Seikyusha, 2016, pp. 163–167. A separate paper on Mihira is in progress.

[10] See Machida, “20-seiki shoto no Tokyo to kyujin kokoku mondai” (Early 20th-century Tokyo and the issue of job posting ads) in Media-shi Kenkyu (Media History) Vol. 46, September 2019.

[11] Nakano, op. cit., p. 29.

[12] In order to cultivate these “key components,” the South Seas Association had been selecting junior high school graduates for dispatch overseas yearly since 1929. In the early 1940s, there were 500 store employees and 70 independent operators, with a total of 800 stores throughout the South Seas; in the late 1930s, quantities handled by Japanese retailers in the Philippines were at half-price, while “significant quantities” were also handled in the Dutch East Indies, and six stores dominated retail in Limbang, Sumatra, with “power not matched even by the overseas Chinese.” From 1941, business trainees were recruited for dispatch (Tokyo-shi Sangyo Jiho op. cit., p. 51). According to research on this point, the South Seas Association was a national commercial migration policy intended by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to overcome the anti-Japanese movement among overseas Chinese; its incorporation in 1939 was a part of a governmental reorganization under general mobilization and a plan carried out by the Foreign Ministry to supervise the Japanese in the South Seas in opposition to the Army and Commerce Ministries and the Planning Board (Kawanishi Kosuke “Gaimusho to Nan’yo Kyokai no renkei ni miru 1930-nendai Nanpo shinshutsu seisaku no ichidanmen: ‘Nan’yo shogyo jisshusei seido’ no bunseki wo chushin to shite” (Aspects of the 1930s Southeast Asia advance policy as seen in the collaboration between the Foreign Ministry and the South Seas Association: Focusing on the analysis of the ‘South Seas commercial trainee system’) in Asia Keizai (Journal of the Institute of Asian Economic Affairs) Vol. 44 No. 2, February 2003). However, as soon as the system of South Seas commercial trainees, intended to expand trading with local businesspeople and sales channels to the interior (in opposition to the overseas Chinese commercial network), was established and began to show results from independent businesses, it was hampered by the restrictions of the Dutch East Indies government. From 1935, the Association expanded its assignment locations to the Philippines and Thailand as well; over the nine years from the system’s launch, some 250 trainees were sent to the South Seas. However, just 44 of them had succeeded in opening their own businesses as of 1940, failing to achieve the initial goals. However, according to the “South Seas Association Business Record” issued after the war, a total of 1,356 trainees had been dispatched by 1944. If this number is accurate, it is true that employees of Japanese-run stores in the South Seas had “sharply increased in number from 1935” and that from the perspective of personnel development, the South Seas Association, under the Foreign Ministry’s control as it was, had run the only personnel development business in the area. It has been pointed out that its “activities were significant” in the sense of collaborating with mainland Japan to conduct language education and local training on site to train personnel to work in commerce in the South Seas (Yokoi Kaori, “Inoue Masaji to Nan’yo Kyokai no nanshin yoin ikusei jigyo” (Inoue Masaji and the South Seas Association southern advance personnel development business) in Shakai System Kenkyu (Social Systems Studies) Vol. 16, March 2008).

[13] “‘Nanpo sodansho’ wo kaisetsu” (‘Southeast Asia Consultation Office’ established), Yomiuri Shimbun, September 9, 1940, morning edition p. 3.

[14] “Aitsugu Nanpo yuki no kibosha” (Increasing interest in travel to Southeast Asia), Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, July 23, 1942, morning edition p. 4.

[15] “Gunsei sokan shiji” (Notice from the Military Inspectorate General), first issued on August 7, 1942. Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei, op. cit., p. 297.

[16] Former Southeast Asia army staff officer/army colonel Ishii Akiho, “Nanpo gunsei nikki (bassui)” (Southeast Asia military administration diary (excerpts), first printed in April 1957. Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei, op. cit., p. 448.

[17] Takeda, op. cit. “Part 4: Southeast Asia dispatch of military government personnel and related trading companies and the early military government structure,” in Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei op. cit., p. 183.

[18] Ibid., pp. 183–185.

[19] Nakashima Yasutsuna with Employment Security Bureau, Ministry of Labor, Shokugyo antei gyoseishi (History of the administration of employment security), Employment Research Corporation, 1988, p. 142.

[20] “Semete choyo de oyaku ni: kessho no shigan satto” (At least let me help through the draft: piles of applications written in blood), Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, August 5, 1942, evening edition p. 2.

[21] “Kekkon sodanjo no shingun” (March of the marriage consultation services), ibid. August 18, 1942, morning edition p. 4.

[22] “Tokyo-to Nanpo sodanjo no kakuju” (Expansion of Tokyo Southeast Asia Consultation Office), Nan’yo Keizai Kenkyu (South Seas Economics Studies) Vol. 6 No. 8, August 1943, p. 68.

[23] “Dai-25-gun Koa Renseijo no setchi” (Establishment of the 25th Army Asian Development Training Institute), 25th Army Command, issued December 24, 1942. Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei, op. cit., p. 183.

[24] “Nanpo kaitaku nomin rensei kikan setchi” (Establishment of a training institute for pioneering farmers in Southeast Asia), Asahi Shimbun, July 1, 1942. Shiryoshu: Nanpo no gunsei, op. cit., p. 183. The Cabinet decision was on June 30 (ibid. chronology p. 554).

[25] Ota Koki, “Konan Renseiin no setchi ni tsuite” (Establishment of the Konan Renseiin) in Seiji Keizai Shigaku (Journal of Politico-Economic History) Vol. 138, 1977, pp. 16–17.

[26] Takunanjuku-shi: Takunanjuku Daitoa Renseiin no kiroku (History of the Southern Development Seminar: Records of the Southern Development Seminar Daitoa Renseiin), Seikei Shinsha, 1978, p. 96.

[27] Ibid., p. 91.

[28] Ibid., p. 131.

[29] Ibid., p. 101.

[30] Ibid., p.161.

[31] Ibid., p.166.

(本文は、2021年7月16日に当サイトにて公開した、町田祐一 論文「1940年代初頭における日本人の「南方熱」の諸相(『報告・論文集』所収)」の英語版です。)